Gábor Takács-Nagy, who will celebrate his 70th birthday next year, learned the art of breath-level precision in ensemble playing as a violinist and as the primarius of the world-famous Takács Quartet. The decades spent in the quartet provided not only artistic experience, but also a way of life: this is where he learned how to listen to another’s intention, how a shared sound is born, and how making music becomes a true dialogue. He later toured the world as a soloist as well, yet he always carried within him that chamber-music sensitivity, which he continues to embody with natural ease in every rehearsal and performance.

As a conductor, he starts from the idea that leading an orchestra is not an exercise of power, but a form of loving connection among musicians. He believes that an orchestra sounds most authentic when its players are unafraid, liberated, and supportive of one another. For him, a rehearsal is not about discipline, but inspiration; his role is not to dictate a path, but to bring to the surface what already exists in the score and in the musicians themselves. One could call this his pedagogical credo: he always seeks ways to elevate musicians rather than to uniform them. This approach proves exceptionally fruitful not only with large orchestras, but also in a chamber orchestra setting.

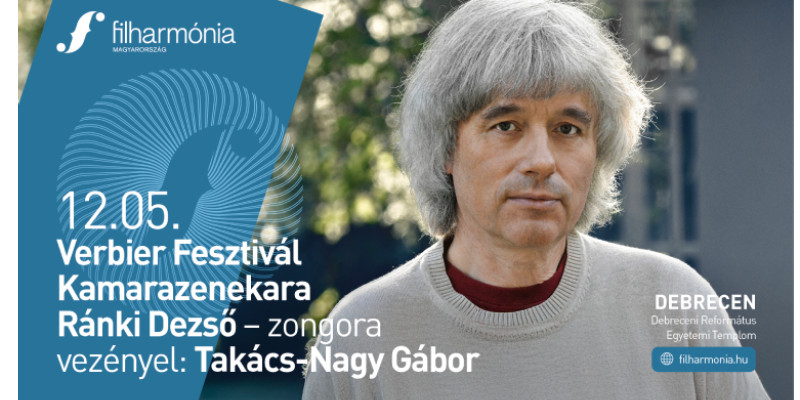

As Music Director of the Verbier Festival Chamber Orchestra, Takács-Nagy can unfold this chamber-music energy to its fullest: the shared breathing built on subtle gestures, the intimacy he brings from the world of quartet playing. Every rehearsal reaffirms that the essence of his leadership lies not in conducting, but in creating community. Even today, the violinist-turned-conductor approaches music with the same humility he had at the beginning of his career: for him, music is not a profession, but the most sincere language of existence. And although he is now celebrated worldwide as a conductor, every movement still reflects the former primarius who believes in the miracle of a shared voice.

At the Hungarian concerts of the Verbier Festival Chamber Orchestra, Beethoven’s Piano Concerto in G major will be performed by Dezső Ránki, who gave his first solo recital exactly 55 years ago, in December 1970. “Not even the most renowned foreign pianist could have aroused greater interest than Dezső Ránki… He is an unusually and admirably perfect pianist. He possesses and conveys musical material with extraordinary security. His entire presence is remarkably likeable; his relationship to music is simple, sincere, and unpretentious,” wrote the legendary music historian András Pernye of that debut.

Over the past five and a half decades, Ránki has drawn a clear, unbroken arc for himself—quietly, without the spotlight—yet he has become an indispensable figure of Hungarian musical performance. He never consciously built his career, a rarity in today’s concert world. He was motivated not by ambition, but by the quiet joy of work. Perhaps this is why his path unfolded so harmoniously: he never forced anything. His reserve is not an artistic pose, but an integral part of his personality. He avoids public self-exposure; what concerns the audience, he expresses on stage, through music. He consistently distances himself from social media, choosing instead family life and the intimacy of personal relationships over the noise of the world. For him, the stage is not a space for self-expression, but for transmission.

His repertoire spans broadly—from Bach and Mozart to Bartók and contemporary music—yet he has never been an advocate of large-scale “complete works” projects. He performs the music that becomes close to him, to which he feels a deep, personal connection; sensing and understanding the composer’s inner motivation is what matters most. Naturally, his view of works has changed over the decades: he would play his early recordings differently today, with greater richness and experience. But the essence remains the same—only more layers have gathered around it. The best moments, he says, are those when the music simply “carries him along” and lifts him beyond any fatigue or uncertainty. He performs only the pieces that nourish him—works that become new experiences with every rendition. “Masterpieces are inexhaustible treasure troves,” he says, “and if they no longer bring new joy, they should not be played.”

What is most exciting in the art of Dezső Ránki is not gesture, but attitude: humility, quiet serenity, and a gentle curiosity about the world. For him, music is not self-expression, not a career, not even an achievement—but a way of understanding.